|

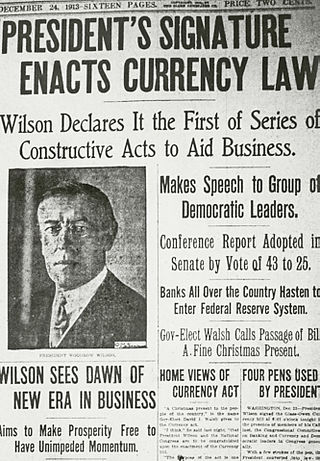

The Federal Reserve System (also known as the Federal Reserve, and informally as The Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created in 1913 with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, largely in response to a series of financial panics, particularly a severe panic in 1907. Over time, the roles and responsibilities of the Federal Reserve System have expanded and its structure has evolved. Events such as the Great Depression were major factors leading to changes in the system. Its duties today, according to official Federal Reserve documentation, are to conduct the nation’s monetary policy, supervise and regulate banking institutions, maintain the stability of the financial system and provide financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions. The Federal Reserve System’s structure is composed of the presidentially appointed Board of Governors (or Federal Reserve Board), the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks located in major cities throughout the nation, numerous other private U.S. member banks and various advisory councils. The FOMC is the committee responsible for setting monetary policy and consists of all seven members of the Board of Governors and the twelve regional bank presidents, though only five bank presidents vote at any given time. The responsibilities of the central bank are divided into several separate and independent parts, some private and some public. The result is a structure that is considered unique among central banks. It is also unusual in that an entity outside of the central bank, namely the United States Department of the Treasury, creates the currency used. According to the Board of Governors, the Federal Reserve is independent within government in that "its decisions do not have to be ratified by the President or anyone else in the executive or legislative branch of government." However, its authority is derived from the U.S. Congress and is subject to congressional oversight. Additionally, the members of the Board of Governors, including its chairman and vice-chairman, are chosen by the President and confirmed by Congress. The government also exercises some control over the Federal Reserve by appointing and setting the salaries of the system’s highest-level employees. Thus the Federal Reserve has both private and public aspects. The U.S. Government receives all of the system’s annual profits, after a statutory dividend of 6% on member banks’ capital investment is paid, and an account surplus is maintained. The Federal Reserve transferred a record amount of $45 billion to the U.S. Treasury in 2009.

History Main article: History of central banking in the United States

In 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony became the first in the United States to issue paper money, but soon others began printing their own money as well. The demand for currency in the colonies was due to the scarcity of coins, which had been the primary means of trade. Colonies’ paper currencies were used to pay for their expenses, as well as a means to loan money to the colonies’ citizens. Paper money quickly became the primary means of exchange within each colony, and it even began to be used in financial transactions with other colonies. However, some of the currencies were not redeemable in gold or silver, which caused them to depreciate. The first attempt at a national currency was during the American Revolutionary war. In 1775 the Continental Congress began issuing its own paper currency, calling their bills "Continentals". The Continentals were backed only by future tax revenue, and were used to help finance the Revolutionary War. As a result, the value of a Continental diminished quickly. The experience lead the United States to be skeptical of unbacked currencies, which were not issued again until the Civil War. In 1791, which was after the U.S. Constitution was ratified, the government granted the First Bank of the United States a charter to operate as the U.S.’s central bank until 1811. Unlike the prior attempt at a centralized currency, the increase in the federal government’s powerâ€â€granted to it by the constitutionâ€â€allowed national central banks to possess a monopoly on the minting of U.S currency. Nonetheless, The First Bank of the United States came to an end when President Madison refused to renew its charter. The Second Bank of the United States met a similar fate under President Jackson. Both banks were based upon the Bank of England. Ultimately, a third national bankâ€â€known as the Federal Reserveâ€â€was established in 1913 and still exists to this day. The time line of central banking in the United States is as follows:

The first U.S. institution with central banking responsibilities was the First Bank of the United States, chartered by Congress and signed into law by President George Washington on February 25, 1791 at the urging of Alexander Hamilton. This was done despite strong opposition from Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, among numerous others. The charter was for twenty years and expired in 1811 under President Madison, because Congress refused to renew it. In 1816, however, Madison revived it in the form of the Second Bank of the United States. Years later, early renewal of the bank’s charter became the primary issue in the reelection of President Andrew Jackson. After Jackson, who was opposed to the central bank, was reelected, he pulled the government’s funds out of the bank. Nicholas Biddle, President of the Second Bank of the United States, responded by contracting the money supply to pressure Jackson to renew the bank’s charter forcing the country into a recession, which the bank blamed on Jackson’s policies. Interestingly, Jackson is the only President to completely pay off the national debt. The bank’s charter was not renewed in 1836. From 1837 to 1862, in the Free Banking Era there was no formal central bank. From 1862 to 1913, a system of national banks was instituted by the 1863 National Banking Act. A series of bank panics, in 1873, 1893, and 1907, provided strong demand for the creation of a centralized banking system. Main article: History of the Federal Reserve System

The main motivation for the third central banking system came from the Panic of 1907, which caused renewed demands for banking and currency reform. During the last quarter of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century the United States economy went through a series of financial panics. According to many economists, the previous national banking system had two main weaknesses: an inelastic currency and a lack of liquidity. In 1908, Congress enacted the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, which provided for an emergency currency and established the National Monetary Commission to study banking and currency reform. The National Monetary Commission returned with recommendations which later became the basis of the Federal Reserve Act, passed in 1913. Federal Reserve ActMain article: Federal Reserve Act

The head of the bipartisan National Monetary Commission was financial expert and Senate Republican leader Nelson Aldrich. Aldrich set up two commissionsâ€â€one to study the American monetary system in depth and the other, headed by Aldrich himself, to study the European central banking systems and report on them. Aldrich went to Europe opposed to centralized banking, but after viewing Germany’s monetary system he came away believing that a centralized bank was better than the government-issued bond system that he had previously supported. In early November 1910, Aldrich met with five well known members of the New York banking community to devise a central banking bill. Paul Warburg, an attendee of the meeting and long time advocate of central banking in the U.S., later wrote that Aldrich was "bewildered at all that he had absorbed abroad and he was faced with the difficult task of writing a highly technical bill while being harassed by the daily grind of his parliamentary duties." After ten days of deliberation, the bill, which would later be referred to as the "Aldrich Plan", was agreed upon. It had several key components including: a central bank with a Washington based headquarters and fifteen branches located throughout the U.S. in geographically strategic locations, and a uniform elastic currency based on gold and commercial paper. Aldrich believed a central banking system with no political involvement was best, but was convinced by Warburg that a plan with no public control was not politically feasible. The compromise involved representation of the public sector on the Board of Directors. Aldrich’s bill was met with much opposition from politicians. Critics were suspicious of a central bank, and charged Aldrich of being biased due to his close ties to wealthy bankers such as J. P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Aldrich’s son-in-law. Most Republicans favored the Aldrich Plan, but it lacked enough support in Congress to pass because rural and western states viewed it as favoring the "eastern establishment". In contrast, progressive Democrats favored a reserve system owned and operated by the government; they believed that public ownership of the central bank would end Wall Street’s control of the American currency supply. Conservative Democrats fought for a privately owned, yet decentralized, reserve system, which would still be free of Wall Street’s control. The original Aldrich Plan was dealt a fatal blow in 1912, when Democrats won the White House and Congress. Nonetheless, President Woodrow Wilson believed that the Aldrich plan would suffice with a few modifications. The plan became the basis for the Federal Reserve Act, which was proposed by Senator Robert Owen in May 1913. The primary difference between the two bills was the transfer of control of the Board of Directors (called the Federal Open Market Committee in the Federal Reserve Act) to the government. The bill passed Congress in late 1913 on a mostly partisan basis, with most Democrats voting "yea" and most Republicans voting "nay". Key laws affecting the Federal Reserve have been:

The primary motivation for creating the Federal Reserve System was to address banking panics. Other purposes are stated in the Federal Reserve Act, such as "to furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper, to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes". Before the founding of the Federal Reserve, the United States underwent several financial crises. A particularly severe crisis in 1907 led Congress to enact the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. Today the Fed has broader responsibilities than only ensuring the stability of the financial system. Current functions of the Federal Reserve System include:

Further information: bank run and fractional-reserve banking

Bank runs occur because banking institutions in the United States are only required to hold a fraction of their depositors’ money in reserve. This practice is called fractional-reserve banking. As a result, most banks invest the majority of their depositors’ money. On rare occasion, too many of the bank’s customers will withdraw their savings and the bank will need help from another institution to continue operating. Bank runs can lead to a multitude of social and economic problems. The Federal Reserve was designed as an attempt to prevent or minimize the occurrence of bank runs, and possibly act as a lender of last resort if a bank run does occur. Many economists, following Milton Friedman, believe that the Federal Reserve inappropriately refused to lend money to small banks during the bank runs of 1929.

The monthly changes in the currency component of the U.S. money supply show currency being added into (% change greater than zero) and removed from circulation (% change less than zero). The most noticeable changes occur around the Christmas holiday shopping season as new currency is created so people can make withdrawals at banks, and then removed from circulation afterwards, when less cash is demanded. One way to prevent bank runs is to have a money supply that can expand when money is needed. The term "elastic currency" in the Federal Reserve Act does not just mean the ability to expand the money supply, but also to contract it. Some economic theories have been developed that support the idea of expanding or shrinking a money supply as economic conditions warrant. Elastic currency is defined by the Federal Reserve as:

Monetary policy of the Federal Reserve System is based partially on the theory that it is best overall to expand or contract the money supply as economic conditions change. Because some banks refused to clear checks from certain others during times of economic uncertainty, a check-clearing system was created in the Federal Reserve system. It is briefly described in The Federal Reserve Systemâ€â€Purposes and Functions as follows:

Further information: Lender of last resort

Emergencies According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, "the Federal Reserve has the authority and financial resources to act as ’lender of last resort’ by extending credit to depository institutions or to other entities in unusual circumstances involving a national or regional emergency, where failure to obtain credit would have a severe adverse impact on the economy." The Federal Reserve System’s role as lender of last resort has been criticized because it shifts the risk and responsibility away from lenders and borrowers and places it on others in the form of inflation. Through its discount and credit operations, Reserve Banks provide liquidity to banks to meet short-term needs stemming from seasonal fluctuations in deposits or unexpected withdrawals. Longer term liquidity may also be provided in exceptional circumstances. The rate the Fed charges banks for these loans is the discount rate (officially the primary credit rate). By making these loans, the Fed serves as a buffer against unexpected day-to-day fluctuations in reserve demand and supply. This contributes to the effective functioning of the banking system, alleviates pressure in the reserves market and reduces the extent of unexpected movements in the interest rates. For example, on September 16, 2008, the Federal Reserve Board authorized an $85 billion loan to stave off the bankruptcy of international insurance giant American International Group (AIG). Further information: Central bank

In its role as the central bank of the United States, the Fed serves as a banker’s bank and as the government’s bank. As the banker’s bank, it helps to assure the safety and efficiency of the payments system. As the government’s bank, or fiscal agent, the Fed processes a variety of financial transactions involving trillions of dollars. Just as an individual might keep an account at a bank, the U.S. Treasury keeps a checking account with the Federal Reserve, through which incoming federal tax deposits and outgoing government payments are handled. As part of this service relationship, the Fed sells and redeems U.S. government securities such as savings bonds and Treasury bills, notes and bonds. It also issues the nation’s coin and paper currency. The U.S. Treasury, through its Bureau of the Mint and Bureau of Engraving and Printing, actually produces the nation’s cash supply and, in effect, sells the paper currency to the Federal Reserve Banks at manufacturing cost, and the coins at face value. The Federal Reserve Banks then distribute it to other financial institutions in various ways. During the Fiscal Year 2008, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing delivered 7.7 billion notes at an average cost of 6.4 cents per note.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia : Wholesale wood and sheet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||